How will China rescue its astronauts? Russia and the U.S. took nine months—how long will it take China?

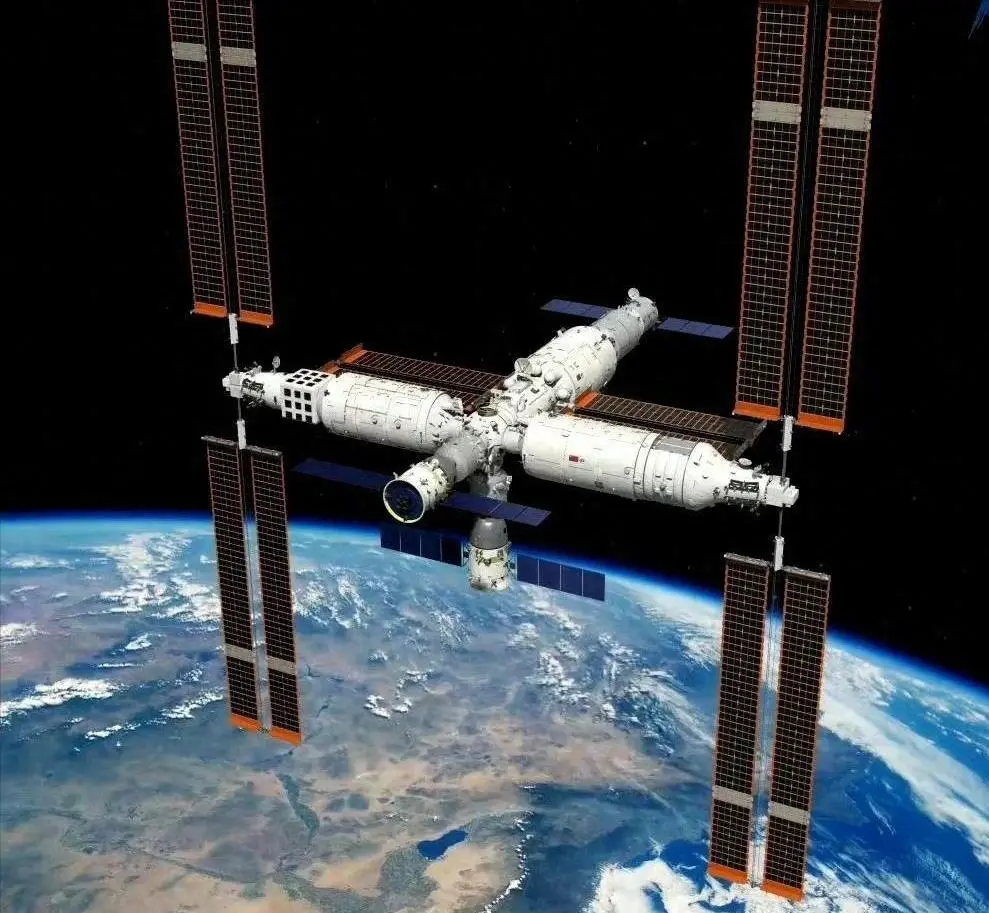

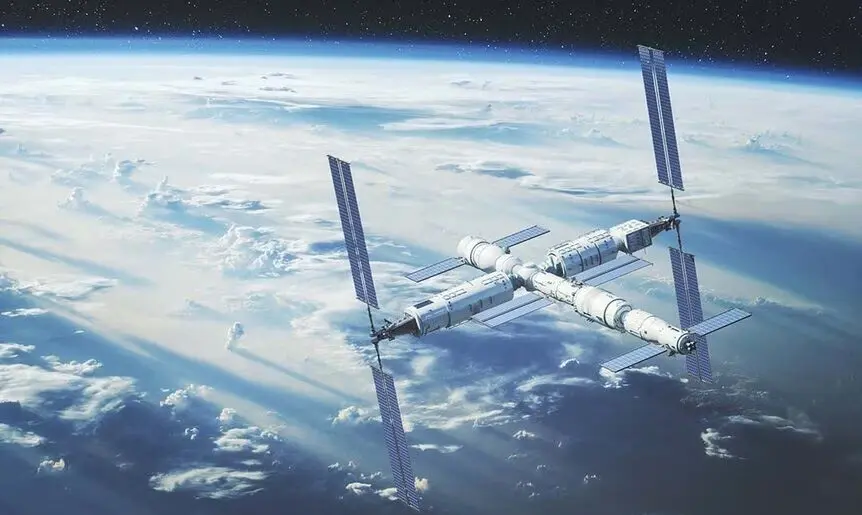

Recently, the world’s attention has been focused on China’s Tiangong space station, orbiting 400 kilometers above Earth.

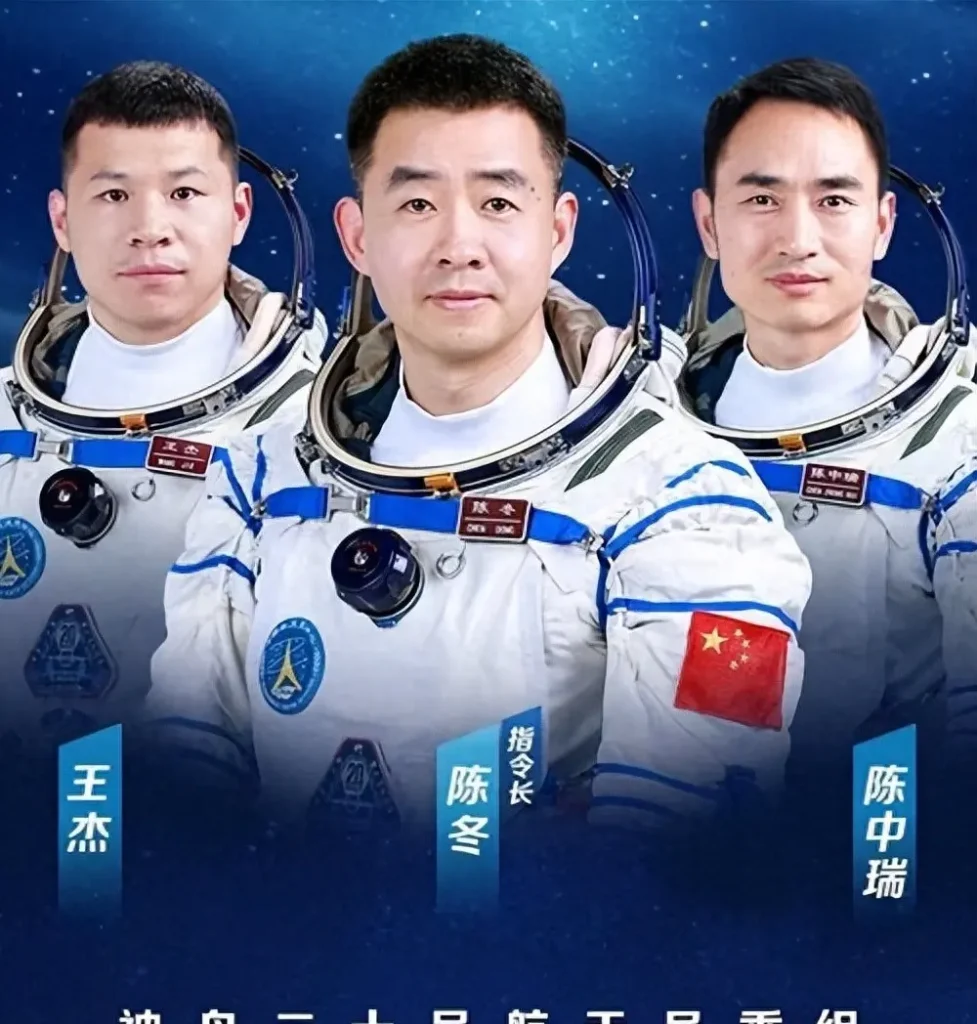

The planned triumphant return of astronauts Chen Dong, Chen Zhongrui, and Wang Jie today was put on hold by an unexpected “space ghost.”

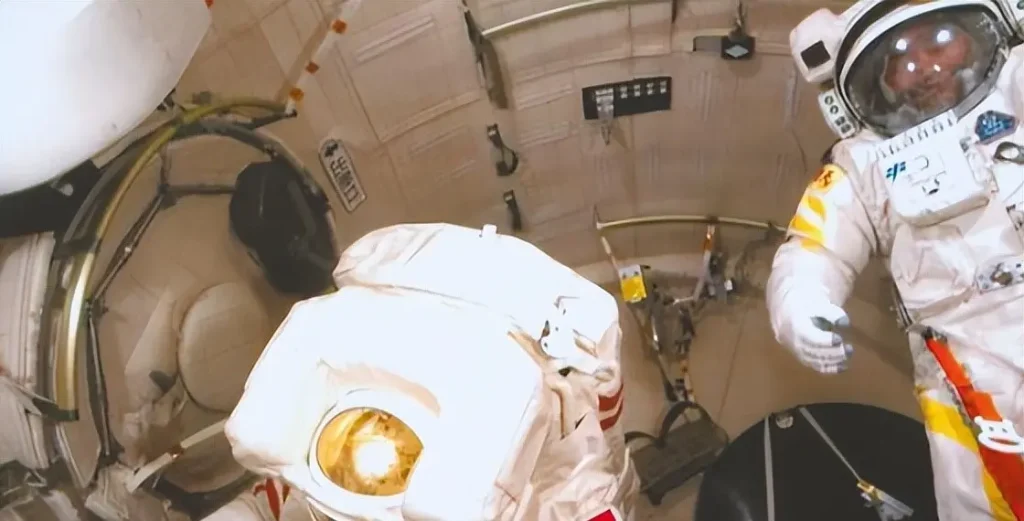

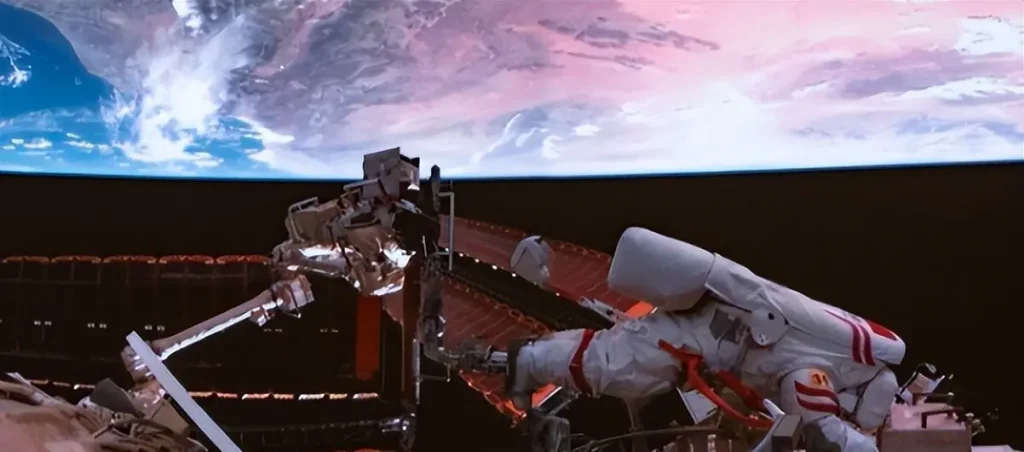

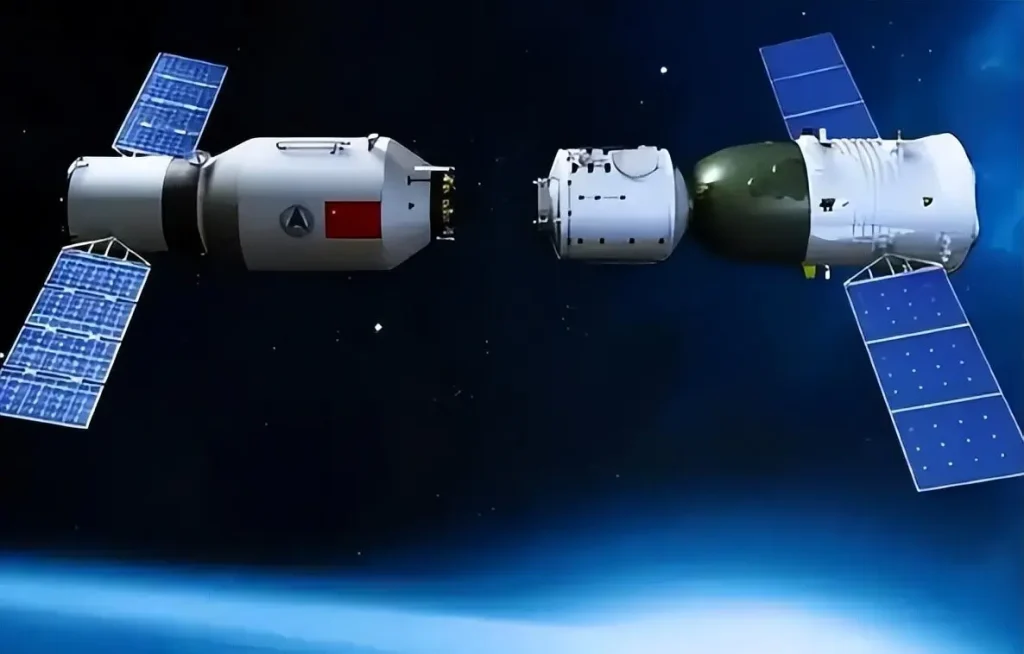

China’s Shenzhou-20 spacecraft appears to have suffered a high-speed impact just before preparing to separate from the space station for its return journey.

This suggests the heat shield of the reentry capsule, carrying the lives of three astronauts, may have been damaged.

If compromised, the capsule would face temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius during atmospheric reentry—an inferno no human body could endure.

The news sent shockwaves through the global space community.

The culprit is likely a 10×8 cm metal fragment from the Soviet Union’s “Cosmos 778” satellite, drifting for 49 years—a deadly killer.

Traveling at nearly 8 kilometers per second, it left a soybean-sized yet potentially fatal “kiss mark” on Shenzhou-20.

Everyone wants to know: What will China do? How long will the astronauts remain stranded in space?

After all, we have “precedents”:

Russian cosmonauts endured over nine months of waiting after a similar incident; American astronauts also endured nearly nine months in space.

Now, it’s China’s turn to answer this challenge.

How long will it take China to rescue its astronauts?

When crisis strikes, a system’s true character often reveals itself in its initial response.

America’s response is commercial tug-of-war, Russia’s is cost calculation, while China’s response was written into planning blueprints over a decade ago.

At the core of this response lies the “launch one, standby one” strategy.

Starting with China’s Shenzhou-12 mission, every time astronauts board a spacecraft for space travel, an identical spacecraft and rocket stand by on the ground in a “standby” state.

This time, Shenzhou-22 will step forward to fulfill the mission.

This is not a project hastily launched after an accident.

On the contrary, while Chen Dong and his crew were still carrying out their mission aboard the space station day and night, the return capsule and orbital module of China’s Shenzhou-22 had already completed final assembly and testing at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, and the Long March rocket had passed all inspections.

All it needed was a command and a few days for fueling.

Some might ask: Didn’t Shenzhou-21 launch just last month?

With astronauts Zhang Lu, Wu Fei, and Zhang Hongzhang already aboard, why couldn’t Shenzhou-21 be used to bring Chen Dong and his crew back?

This is a valid question, yet it precisely highlights the meticulous nature of China’s space rescue system.

Every spacecraft docked with the space station serves as the current crew’s “lifeboat.”

If Shenzhou-21 were used to retrieve the Shenzhou-20 crew, the three astronauts—Zhang, Lu, and the others—left behind on the space station would instantly lose their life support.

Such a “robbing Peter to pay Paul” scenario is absolutely prohibited in China’s aerospace contingency plans.

Therefore, the answer is already clear.

Once ground assessments confirm the return of Shenzhou-20 is too risky, Shenzhou-22 will initiate launch procedures at the earliest possible time.

How soon is that?

According to China’s officially disclosed procedures, routine emergency preparation takes approximately 7 to 10 days.

This means that within half a month, a brand-new “space lifeboat” could arrive at Tiangong to safely retrieve the three astronauts.

This stands in stark contrast to the months-long waits often required by the U.S. and Russia.

Why Are U.S.-Russia Rescues So Slow?

Without comparison, the value of China’s system remains unappreciated.

Let’s rewind to two famous space rescue incidents and examine what unfolded behind those nine-month waits.

The first was the Russian Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft incident in December 2022.

A tiny debris fragment less than 1 millimeter in diameter precisely pierced the spacecraft’s radiator, causing coolant leakage.

Without the cooling system, the return capsule would become an “oven” upon atmospheric reentry.

Following the incident, the Russian space agency faced a critical decision.

They possessed the capability to launch a new spacecraft for rescue, but this would incur the cost of an additional launch.

Ultimately, after repeated deliberations, they opted for an “economical solution”: the stranded three astronauts would “work overtime” aboard the space station for over half a year, awaiting the next scheduled rotation mission to return home aboard the new Soyuz MS-23 spacecraft.

Thus, the originally planned six-month mission was forcibly extended to a full year.

The astronauts didn’t return to Earth until September 2023, spending over nine extra months in space.

Each day of those nine months brought potential risks to the space station and endless longing for their families.

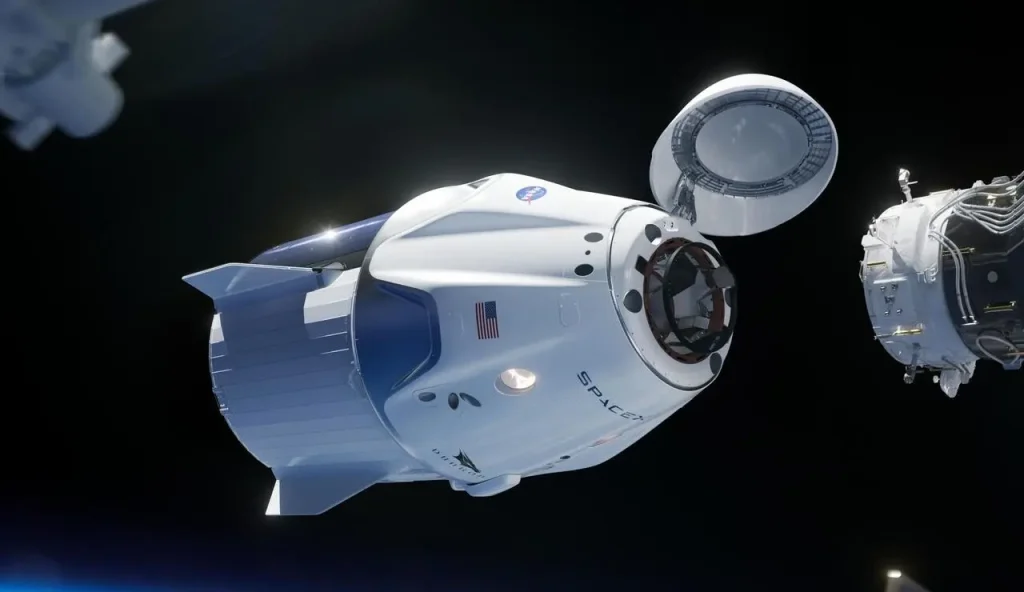

The second incident occurred in 2024 with the U.S. Boeing Starliner spacecraft.

This highly anticipated commercial spacecraft encountered multiple failures during its first crewed flight, including multiple thruster malfunctions and persistent helium leaks.

Two veteran astronauts—62-year-old Barry Wilmore and 60-year-old Sunita Williams—found themselves stranded at the space station.

Their journey home became a chaotic stew of commercial, political, and technical challenges.

Boeing itself couldn’t dispatch a second spacecraft on short notice.

Who to turn to? Bow to rival SpaceX, or seek help from Russia amid delicate relations?

Days slipped away amid hesitation and coordination.

Ultimately, NASA decided to have SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft carry out the rescue mission.

But a new problem arose: the Dragon’s limited seating capacity meant retrieving these two astronauts would leave the U.S. crew on the space station understaffed, unable to complete scheduled scientific tasks.

Thus, they had no choice but to wait until the next crew arrived in March 2025 to hitch a ride home.

What began as an 8-day mission turned into nearly 9 months of drifting in space.

When Sunita Williams reappeared in public, media captured her visibly haggard appearance, raising concerns about her health.

These two cases—one trapped by cost constraints, the other by commercial competition—

This unexpected collision posed a severe test for the Shenzhou-20 crew, yet it became an unforeseen “real-world test” for China’s entire space program.

The world is watching to see how China will deliver its response in this race against time.

The answer may unfold within the coming weeks.

发表回复